Building a Research Culture

How I changed my own mind about what "research" is and should be

Rejection after rejection, I began to suspect that I was doing something wrong. I identified my tendency to impose my idea of “research” in all my conversations, reading job descriptions, and doing job interviews as the main culprit. I realised that my idea of “research” was different from “research” in the UX industry complex. It took four big rejections from applications-that-matter (what a waste!) to help me reach this point.

We were all speaking about “research” in different wavelengths even if we were using the same words and talking about similar activities. An example here is the statement from an actual job description, “you’ll conduct primary research; exploring the emotions, behaviours, and motivations of our users, and then work with teams of designers, Product Managers, engineers…” are perceived differently by team members and recruiters. While we were talking about the same thing — words such as “exploring the emotions of our users,” “conduct primary research”, these actually refer to different mindsets and frameworks that are somewhat alien coming from an academic point of view.

This lightbulb moment came about simultaneously because, aside from doing interviews with different recruiters, designers, and managers from different companies, I was also engaged in a project with Dr. Erin B. Taylor on building healthy research cultures. What were two different life domains quickly converged into a singular problem — the misunderstanding of research practiced by specialists and practitioners in the industry.

This post discusses my personal breakthrough from misalignment to re-formulating how the “research” process must move from the “I” (lone research expert) to a “We” (all are experts or researchers) and create a practice to scale for our teams and organisations.

This post is divided into three parts. I first briefly look at my own roots and my research mindset development from my institutional and university training. I use the linear flow in the double diamond design visual model as a conceptual similarity to the simplified scientific method. In the second part, I turn to the DevOps groups that tackle a similar problem labeled the “hero culture.” This is a software development pattern, often exacerbated in the open-source community, using a lone expert or gifted player to troubleshoot problems to the detriment of building group accountability. In the final part, I propose a new research visual model that can help change one’s personal mindset for the industry context.

The “I” in Research. The “hero culture,” or the lone troubleshooter, in the research world, the expert, is seen as having the exclusive training, skill, talent, or capability to undertake problem-solving. After all, this is the premise in university training — to hone individual skills of problem identification, investigation, and finally, insight conclusion and communication.

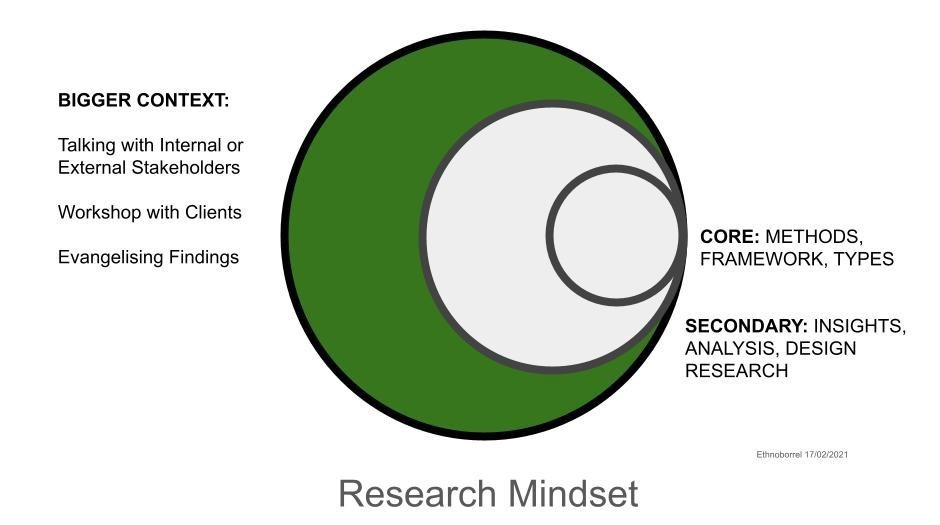

The research mindset is typically expressed as an outward fanning of the individual thinking and working process of specialists (see figure below). You can visualise this simplified “I” research mindset model as closed concentric circles having two cores of individual priorities — the central core which houses individual competencies such as socialised and specialist training in methods, frameworks, and theories; and, the secondary circle where investigation, analysis, and conceptualisation occurs. This research flow is akin to the flow of a scientific method of investigation embedded within the person and body of a researcher. Once the two core processes have been done, it is now time to present the results to the wider community.

The “I” mindset traditionally leans on a heavily siloed approach because the identity and work process of research is housed inside the individual bodies and brains of researchers. In the mindset model, knowledge is expressed in the solid lines of the individual core and moving outward to the stakeholders and audience only once this initial process is done. Research collaboration in academia is rewarded in writing grants but at the micro-level, this occurs in the secondary core practice once the research is done.

What happens when this “I” research mindset reproduces in the industrial setting? This two-stage process from “I” before the “We” produces a lot of miscommunication and misunderstanding of what “research” really is. I’ll use the double diamond model as a visual anchor to this discussion and identify how the confusion occurs between specialists and practitioners occur in practice.

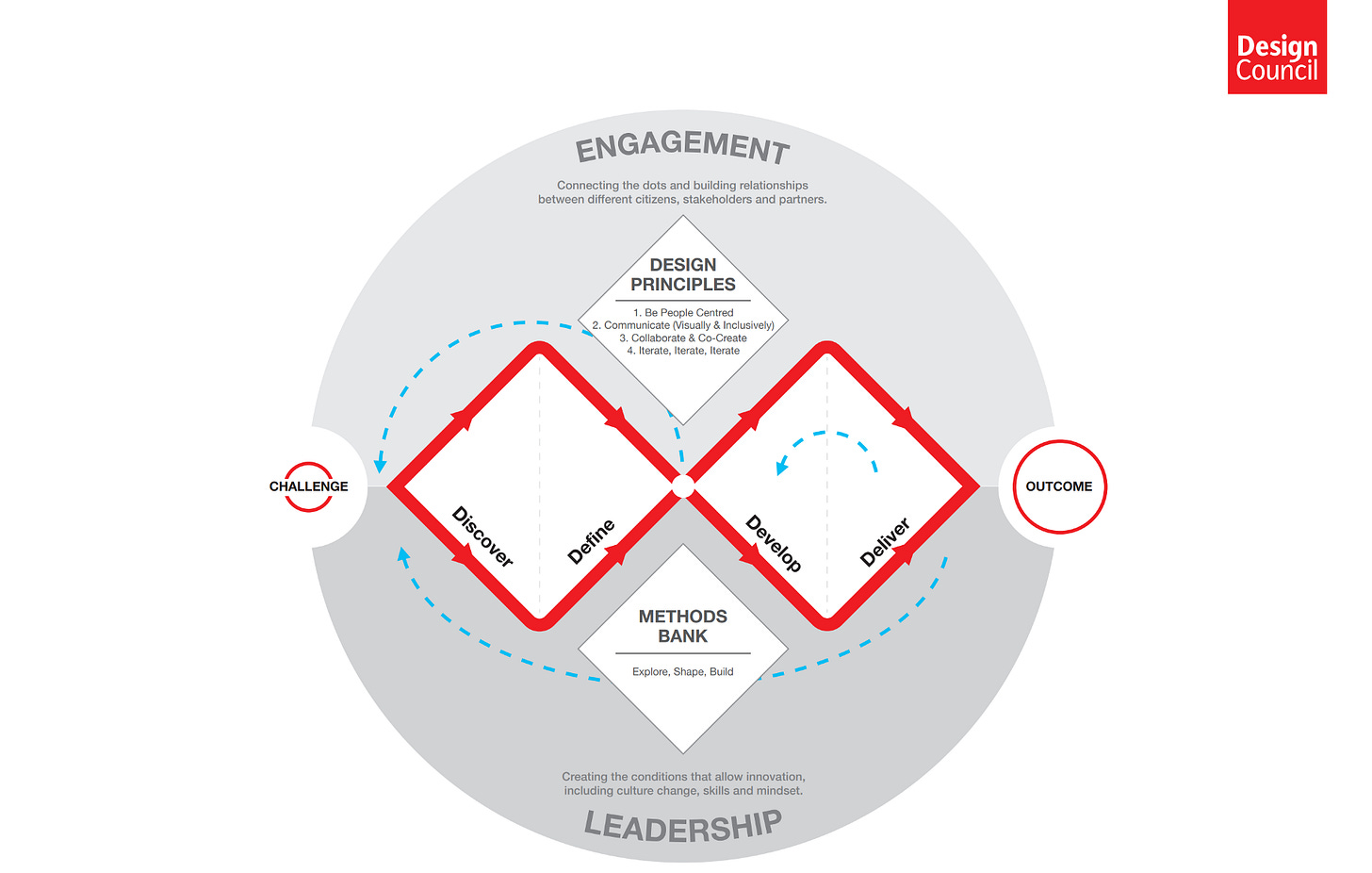

Context: Locating Research in Industry. I use the double diamond diagram as a stepping stone to examine the “I” mindset in research practice. This model is from 2007 in which the British Design Council reconstructed the process by which product designers successfully built and launched what turned out to be iconic eleven products. Chief Design Officer, Cat Drew (2019) of the UK Design Council revisited the model and how it became an important tool to explain the design process to non-researchers. This is what makes the double diamond significant as a common reference. I use this as a generic visual framework (1) to communicate the design process (2) and to locate where researchers are in companies and teams.

This diagram is useful to examine how “research” is understood by industry practitioners based on its positions in the product or service development work process. One of the ways you can assess a company’s understanding is by reading the job descriptions for roles in UX Research, User Experience Researcher, UX Designer (and variations of that title) and how these slot into variations of a similar process.

In this diagram, researchers may be located in the (design) solutions space — as usability testers and validating products. Or researchers may be tasked in the problem space (research) in the areas of discovery and problem definition. Having this visual placement will help you clarify what “kind” and “type” of research that people are talking about. These visual and conceptual references have helped me build a “shared language” by recognising and enquiring how researchers and designers work together.

Where’s the “I” here? This diagram illustrates how researchers can misinterpret what “research” is in this process. Without changing the “I” mindset, a researcher may think the discovery and exploratory phases rely on them as individual persons working on their own. While this makes role making clear between two parties, this visual format may mislead those new in the design process as inherently a siloed, bounded problem identification expertise. Furthermore, the points of interaction slots in well with the phased core and secondary model of doing “I” research — you collaborate with designers after the micro-level thinking process. This mindset is ego-focused and resists further collaboration. Collaboration is a non-standard practice especially since in a discipline like anthropology, research and insight formation, are embodied into the bodies of researchers. When transferred into the industry setting, there is a tendency to reproduce this epistemology (knowledge formation) within teams.

Consequences of the “I”: Linearity — One of the accusations leveled against the double diamond model is the linear approach like Leon Gauhman (2018) who rightfully identified the linear flow as suitable for a manufacturing environment rather than a software development work process. The linear way of doing things relegates the software team “behind” in the development rather than in front or co-creating at the early stages as in the common case in service design. This is what Kate Ivey-Williams (2017) identifies as “death by double diamond” in which service designers like her pass off their design studies to the client who fails to execute the project and is akin to what she describes as the waterfall type of development.

However, I argue here that seeing linearity and the positional injustice that results from the design process is the epistemology of individual research and not necessarily from the double diamond approach. If there is only the lone expert with no system or culture to propagate expertise across teams, then designers or developers end up frustrated by being excluded at the design “font-end.”

This common model misinterpretation has since been corrected in 2019 by the Design Council explicitly adding collaborative design principles and methods into the process. However, it remains to be seen whether the new yet clunky visual model will catch on as with the old one.

How do we form a traffic of collaboration between individuals and among individuals in what are inherently individual-based research initiatives? I turn to the software development groups who are grappling with similar problems by organising systematic, transparent, and accountable software development operations (DevOps). The all too real burnout and “hero culture” plaguing developers also confront the research operations.

Hero Culture as Crisis Mitigation Culture. One of the central problems plaguing software development and maintenance is the “hero culture,” or the elite few like the Cult of the Dead Cow (cDc)who swoop in to solve problems in cybersecurity or maintaining the open-source code community reported by Nadia Eghbal in 2016. Some of the common consequences have been documented by the Berlin Maintainerati in 2019, including individual burnout, abusive work practices, and inclusivity rather than a systemic onboarding and delegation of tasks to other actors in the community.

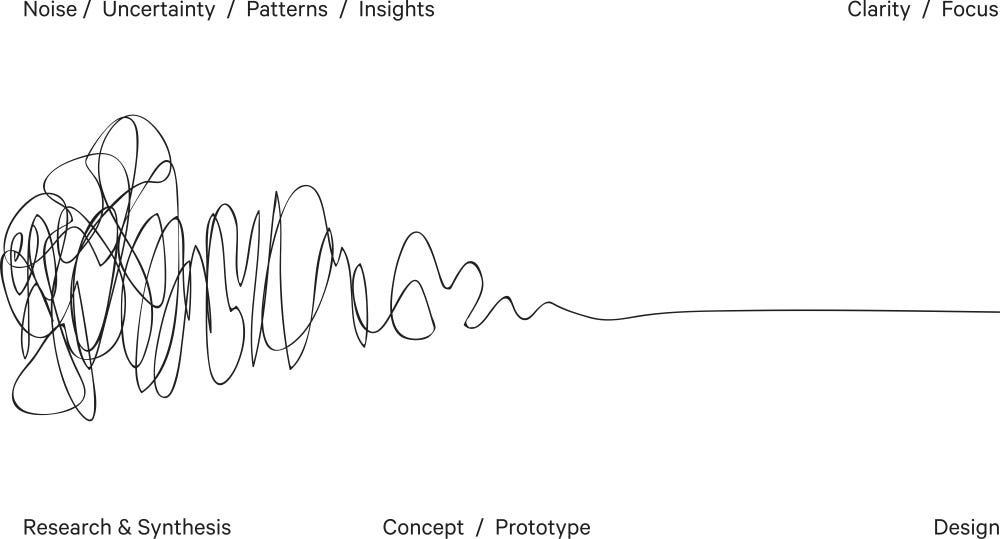

From Crisis “I” to System “We:” Fusing Researchers, Designers, Product Managers, with Software Developers. When it comes to teamwork, fusing different thinking and working models becomes the next frontier. Product development with software developers at the helm also struggles to fuse together user insights into their work process. Practitioners are realising that the process is messier and the opposite of the rigid diamond model. Jens-Fabian Goetzmann (2019) realises this in his job as a product manager working with product designers. He describes the process as akin to the design squiggle of Damien Newman.

Software companies look to models used by top firms such as Google’s UX Design Sprint to institute a more robust and inclusive practical design and have reinterpreted them to their own practice and clients.

For instance, Dylan de Heer (2018) proposes a circular reinterpretation of a software development practice. In his diagram, the UX Design sprint forms the core and is embedded within the double diamond principles of discovery, define, ideate, and develop. Within each of the four components are the twin elements of tools and methods. In the research/discovery phase, he has outlined some of the co-creation tools used such as user journey mapping and empathy mapping among others.

The circular model makes it hard to visualise how different components such as the interaction between non-developer team members.

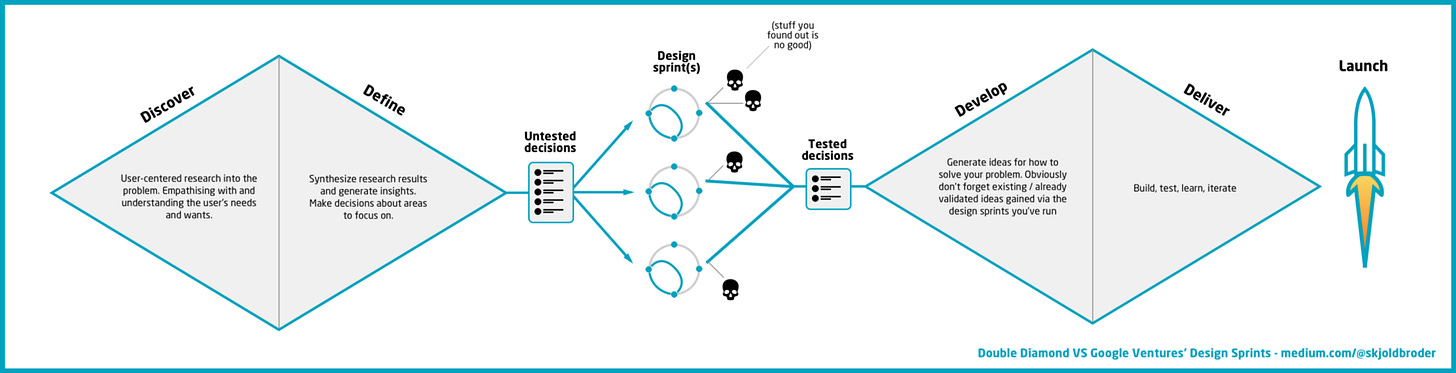

This is where a more linear interpretation by UX designer Skjoldbroder makes the relational process visually clearer by integrating the double diamond with the Design Sprint. In his diagram, he added the design sprint as a learning and testing phase in between the double diamond. His process flow model visualises the different roles of a team and the cooperative process that happens among members.

The two models attempt to envision and fuse a work process that recognises the different work and thinking processes of two different groups: the “researchers” and the “non-researchers.” The common link between these two groups is the shared design process goals which aim to solve a problem. “Research” is simply understanding how to look for answers to questions and not a specialist exercise. “Research” is actually a task done by all members of the team. In this way, thinking of research as simply just in the “front-end” or “back-end” or scrapped altogether due to cost-cutting is an example of the individual expert mindset. This same mindset can skew your understanding and reading of the job description of UX or user experience researchers.

If I want to change the conversation of research, then I have to let go of the idea of the lone research expert and start moving towards research as building participatory and transparent processes. Research democratisation occurs right from the beginning similar to the DevOps community and not towards the end. This requires a mindset shift from an “I” to “We” especially for research specialists like me.

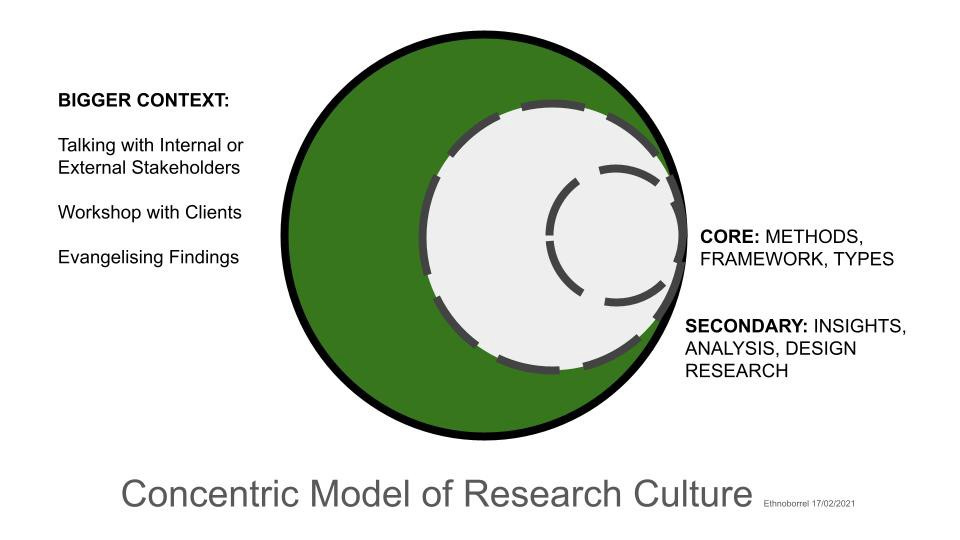

This is the first roadblock to building a research culture — research defined as an individually skilled researcher versus everyone enskilled as researchers. This re-reading of the siloed diagram now breaks down the solid lines into dashed lines around domains that were once highly valued in an individual practice.

The core area of methods and frameworks is what has been drilled as valuable and a “trade secret.” In an organisation that has low research maturity, a research practitioner may feel that he or she must cultivate and sustain their individual hero persona and guard it fastidiously, to prove their value and uniqueness. In doing so, this walled-in approach may benefit individuals in the short term but hurt teams, the organisation at large, and ultimately, oneself in the long-term because any insights and processes cannot scale.

To break down the core, the practitioner has to replicate him or herself by training others. One has to give up control and monopoly of skills around “research” and seeing it as a “trade secret.” By reproducing and teaching others to become researchers themselves, relieves the practitioner from being overburdened and will communicate the value of research. The other employees will now be taught how to seek answers to their questions and perhaps, consult with the practitioner.

Moving to the “We” epistemology around insights sharing requires broadening the “research” methods to include co-creation workshops. These techniques democratise the research process by building stakeholders’ trust, empathy, and investment into the research problem and insights creation. Research as workshops greatly reduces distrust with specialists, relieves misunderstanding of “research,” and potentially achieves consensus and acceptance among the stakeholders.

The breaking down of barriers does not diminish individual practice but actually redirects specialist knowledge as part of inner core work. The cultivation of skills and inner practice retains its individual approach and requires an active community of like-minded practitioners to nurture. In a sense, all that happened is the reduction of “I” into inner core research and expanded the “We” research as the new norm.

For a research practitioner like myself transitioning into industry, my former training and epistemology (how to acquire knowledge) were leaking into my job interviews and with frustrating results. However, once I identified that this was the cause, I was humbled by the realisation. I have since shifted my mindset about research and have since advanced in the job interview process. With that out of the way, I can now concentrate on building a shared language by learning new “We” skills.

Postscript: There are other models that outline working, thinking processes, relationships, and concepts made by Hugh Dubberly of Dubberly Design Office. It is a great art and intellectual library! Thanks, Hugh for building and sharing!