Addendum: David Graeber's Notes on the Violence of Equivalence (Part 1)

and his vision for a human(e) economics

Dear Readers,

I traveled through time zones geographically and mentally back to one of my working desks in the last decade or so. My room has been furnished with my now-deceased aunt’s furniture. I coveted her wide flat writing table in their old house. I became the caretaker when my aunt left for America and finally, its owner. This is one of the reasons I even bother to return to my old room and clean it after years of neglect and non-use. Furniture loves to be used. The wood was thirsty. Very thirsty. Parched. It needed attention. I needed it as much as it needed me.

Whenever I write in this narra (Pterocarpus indicus) table, it transports me back to the glory days of handwriting and long focus. I hope that it will help me with this week’s big challenge: to understand the main points of Graeber’s concept of violence of equivalence.

After four chapters, Graeber argues that:

1. there is deep-seated violence in our commercial systems

2. the origin of violence in our commercial system can be attributed to the false equivalence between human needs and quantified debts (the accounting problem)

3. we must unearth this false belief that we have acquired about our understanding of money, human needs, and debts

4. only then can we propose to redefine what makes for a more human social life

A tall order for a book. I thought he did the explanation poorly since he tends to go off-tangent. It helps to go off-tangent myself and dive deeper into his ideas from another pathway. Luckily, he explicitly explains these four points in the first third of his journal article, On Social Currencies and Human Economies: Some Notes on the Violence of Equivalence published in 2012, right on the heels of the book publication.

Vision of a Human(e) Economy

I was surprised that this paper paved the way for me to re-think our economic life and remove ourselves from the grip of a capitalist/consumerist economic framework. His first mandate is to redefine economy as a discipline by reversing its focus: a focus on the adjustment or transformation of human relations as its primary goal rather than allocating commodities (i.e. people first before things). This is what he calls as the human-based economy (human economies).

Social currency as transforming relationships

What does it look like to focus on understanding the role of money in transforming human relationships? Fortunately, anthropology provides some real-life answers when it comes to money. In the anthropological literature, you may find money as we understand it in the form of beads, shells, cattle, pigs, salt, or other materials or animals. They are not necessarily money or coins as we recognise it but they could be different materials that can represent any agreed-upon value that incidentally doubles as an exchange mechanism. Here, exchange for commodities is a secondary function.

In this human-first economy, the participants understand one key point, and this is where people like us from money or coinage societies may misunderstand:

there is an incomplete substitution between human beings and the prevailing currency

That is, while objects may take the place of humans, this value conversion is partial or not representative of the person. Now this is an important point. When participants understand that any object cannot compensate for human needs, then people are able to distinguish what Graeber calls irredeemable and redeemable debts.

Purpose of money

In the human-first economy, the participants recognise that currencies have a social component and a commodities exchange component. It is important to point out that the participants do quantify transactions and relationships. But it is the way they understand money and its uses that make it non-violent.

This non-violent social-first money is called primitive money1 in the anthropological literature. Primitive money is heavily biased towards the social component. What’s interesting though is that primitive money both occupy the conceptual spheres of commodities and social obligations. Graeber argues that in such a context, the social participants understand that the same currency can stand for redeemable and irredemable debts. This is where the difference lies.

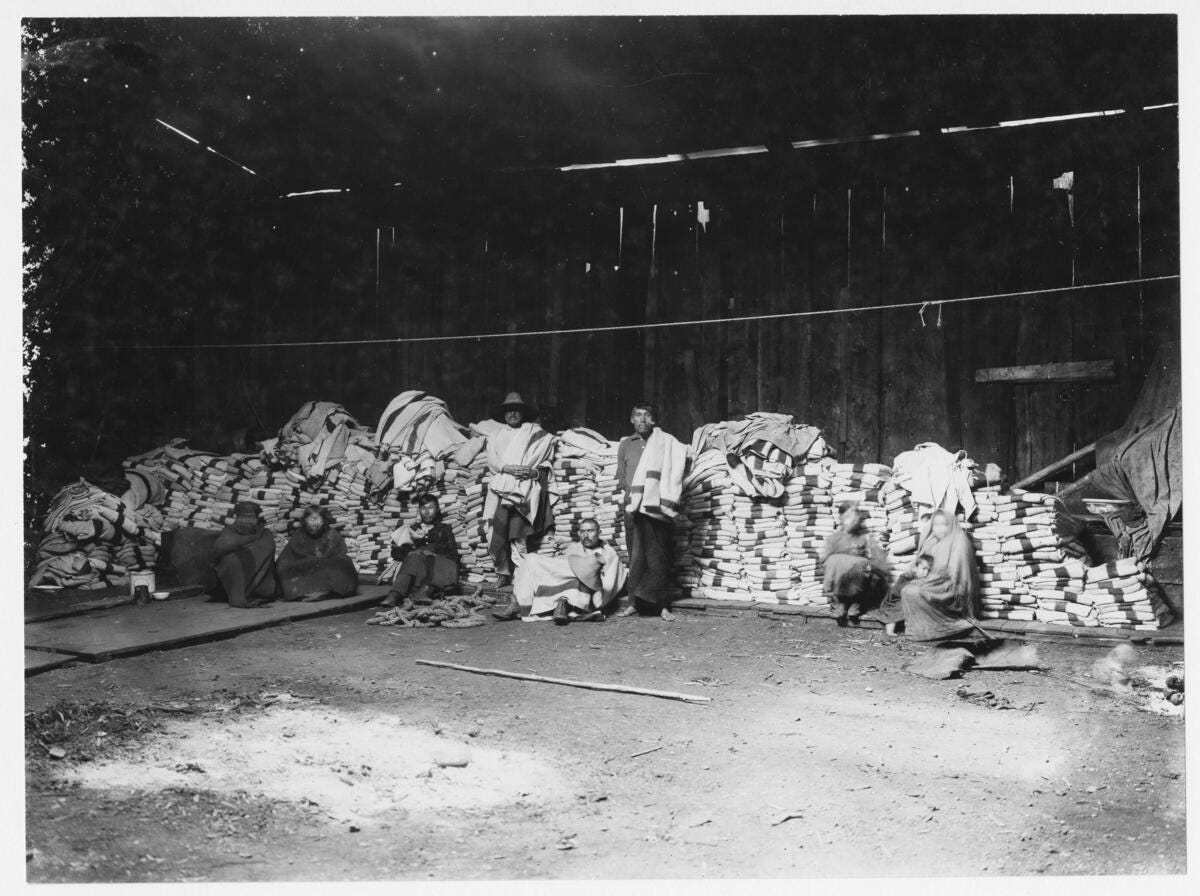

Graeber defines redeemable debts as transactions that can whittle things owed down to zero. Clearly, we see this in the trade for blankets for other desired goods even in a ceremonial context in which status ascension and celebration occur. This transaction is a financial computation of value represented by blankets.

More significantly, Graeber argues that social participants also use primitive money to pay off irredeemable but are nonetheless payable debts, with the understanding that there is incomplete substitution. This means that primitive money, in contrast to capitalist money, cannot fully cancel debts between transacting individuals or groups.

In contrast, Graeber argues that our current contemporary capitalist money and system ignores the difference to our detriment. Capitalist money flattens all human relationships and transactions into redeemable debts. Consequently, he argues that the reduction to zero across all types of transactions lead to the violence of equivalence.

It is this conundrum over the purpose of money and a system of social debt that Graeber is tackling in his book.

Round Up

Graeber formulates his human(e) economy by arguing that there are two key financial value computations:

irredeemable debts that humanise quantified transactions because any payment done is with an understanding that it cannot be fully paid or truly substitute a human need

redeemable debts that potentially degrades the human condition and engenders violence when all transactions cancel any relationships through total cancellation to zero.

It is a danger for any economic system to focus on only redeemable debts for all types of transactions. The purpose of money is its transformative aspect of human relationships. This is missing in a predominantly capitalist money system in which the race is towards accounting zero. In the next post, we will continue looking into how Graeber dispels false debt/money beliefs in the Western tradition.

It has taken me several human hours of reading, pausing and reflecting (including 12 hours of flight time) to even make sense and follow Graeber’s thinking. I would appreciate if you can express your support to slow reading and thinking by subscribing!

Graeber uses local currencies as a placeholder for primitive money in contrast to state money in Melanesia. For purposes of clarity, capitalist money is the term I use to refer to the coin currency we follow in our commercial system. I will retain the use of primitive money or social money for clarity. My choice to use primitive as a term is contextual. When the literature or the context uses it, I will use it for consistency. This term is no longer in use by anthropologists and do not imply the pejorative term by its use.