Addendum: David Graeber's Notes on the Violence of Equivalence (Part 2)

and the origin of false equivalences in money and debt

Living in a capitalist consumerist system, it seems hard to think outside of it. I came in thinking that just like good fences, debt cancellation makes good neighbours and friends. In the previous post, David Graeber proposes the opposite: a human(e) system built around a social credit system (a social debt). Let’s see how his formula makes for good neighbours.

Operationalising the human(e) economy

In a human(e) economy, outright debt cancellation does not necessarily make for good neighbours according to Graeber’s calculation. It is because we lost sight of what money should be, as an

an abstract unit of account to support credit systems than as an actual ‘medium of exchange’

This redefinition means that there is a more nuanced understanding of debts that consist of redeemable and irredeemable components that money can and cannot cover. The lack of awareness of these two aspects is what causes violence in our systems.

In the next sub-sections, I will discuss how Graeber answers why we no longer have such viewpoints and how he conceives the potential in our systems.

The origin of money was a social debt system

Prior to our capitalist system, money was a way to quantify social responsibilities which we understand as debts (or a time delay system of compensation). Thus, people understood virtual money first before the advent of any physical currency as previously discussed by Graeber. In this system, money, he continues, are conceptual placeholders of precise proportion values whether or not these concepts exist in a physical currency. This pre-established unit of value makes it easier to determine how much iron could be quantified against the grain as a dummy example.

The struggle of people lies in a currency that can quantify equivalence for redeemable and irredeemable debts and later on follow the same logic to exchange— responsibilities first before goods.

This social debt function of money has not been more mainstream because Graeber argues that the origin of money/debt hypothesis has been mixed up into another body of theory he labels as the primordial debt theory.

The West’s irredeemable debts

Why is it necessary to digress into the primordial theory of money? I think that by including a discussion on this, Graeber shows that Western societies also have their concept of irredeemable debts despite his overwhelming emphasis on redeemable debt transactions.

Unfortunately, Graeber points out several problems and consequences with the current myths of the primordial theory of money.

we feel that we owe a debt to society

we feel that society/government has the right to extract or represent us in debt payments

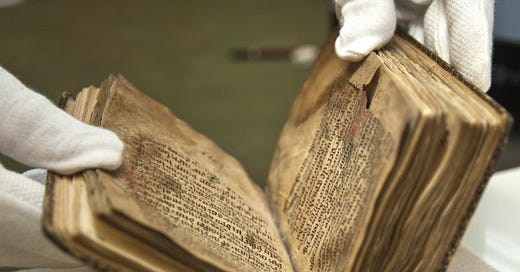

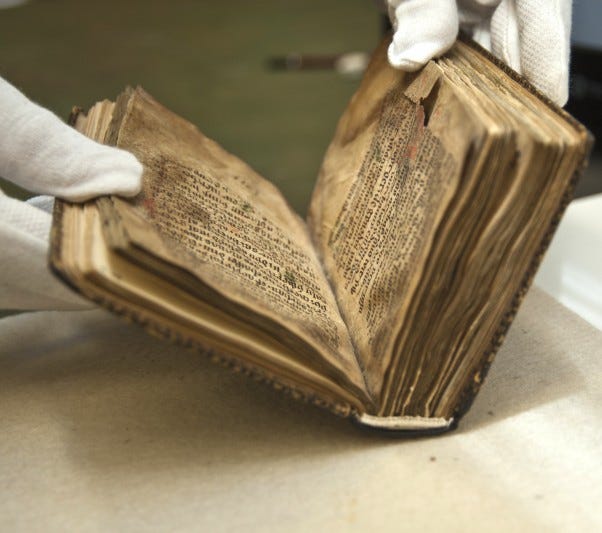

Graeber spends a great portion of the first two chapters debunking and unearthing why this myth persists. Another observation that I have made is that Graeber tends to ignore any spiritual component to any of his thinking and he is clearly focused on secular and social grounding. Therefore, he quickly discounts any supernatural and spiritual conceptual formulations of human debt. He traced our current understanding of irredeemable debt to Vedic and Homeric texts. His main criticism is that none of these texts are rooted in any lived realities. There is also an absence of any ethnographic evidence to support these sources.

(picture)

In the Vedic/Homeric origins of the debt/money relationship, Graeber posits a three-step hypothesis on how the Western concept of irredeemable debts happened.

In this origin of debt/money,

money originated in sacrificial ritual

taxes are a secular interpretation of the debt that we owe to the gods but now re-interpreted as what we owe to society

this debt to society would then be translated into specific debts to individuals.

From sacrifice to the gods (irredeemable debts to the gods) to its translation to societal debt (irredeemable debts to society), Graeber believes this to be the mirror of Adam Smith’s formulation of the myth of barter. Smith’s theory of money postulates that barter came before money and money arose because of convenience. If Smith established the framework for the West’s redeemable debts, the primordial theorists established the origin of irredeemable debts. Both of these formulations had a profound influence on the current paradox in capitalist currency societies: how all debts can be paid yet we feel we owe a lingering debt to society.

Conceptualising social currencies

By teasing out the West’s concepts of redeemable and irredeemable debts, Graeber has exposed the false value equivalences between our use of money and how we understand debt. Graeber proposes to re-orient proportional values in a human(e) economy.

The key here is that there is no one way to do it.

We find different and adaptive cultural responses to this tension in the anthropological literature. This is the critical challenge facing each culture and societal group: balancing uncertain equivalences between social obligations, social needs, and consumer/commodity exchanges.

In the next few weeks, we will look at two ethnographic cases of social money and how people managed proportional values, social obligations, and currency.

Graeber asks, how did we end up losing social money? What happened in human history? How did we lose a human-first approach to economics?

Round Up

Debt cancellation alone does not make good friends. Graeber argues that social debts consist of:

redeemable debts

irredeemable debts

Money’s function is to primarily support a proportional values equivalence framework that varies between cultures. Social money has to be able to pay both types of debts. Due to our overwhelming emphasis on debt cancellation across all credit systems, we reproduce a false equivalence between money and irredeemable debts that potentially give rise to structural and social violence.

Ironically, there is no zero debt. No matter our intense debt-cancellation approach to money and social life, it is hampered by a feeling of irredeemable debt to society. It is this extreme eternal obligation that Graeber traced to Vedic and Homeric texts without basis historically in human social life. The Western condition is characterised by such a paradox — the fight for zero value equivalence yet in a perpetual obligation to a theoretical society/government.